There is a very long, very old bridge that I can see from my spot at the library. It crosses the Loire river, which is not unlike the Red River in both its speed and colour. The bridge is called Pont Wilson. Wilson is probably someone’s name and since everything here is named after someone, it’s probably named after this guy Wilson, but I don’t know who he is or what he did. I could look it up, but I’m not going to right now. This bridge is pretty wide and what’s funny about it is that they’ve only designated one lane for vehicles. So if you’re a car and you want to take the bridge south to head towards the city centre, you’re cool, but if you need to cross the Loire heading north, you’d better find another bridge. The middle part of the bridge is reserved for the trams which run north and south. You can walk on that part, but you’d have to move out of the way a bunch so as not to be hit by a tram. They don’t go too fast, but they weigh a lot and if they hit you you’d probably feel pretty stupid. Plus there’s a huge portion of the bridge reserved for foot traffic and a whole separate portion for bicycles. This way everyone gets fair use of the bridge. Except for cars. Like I said, they get one lane. But you know, cars have it pretty good everywhere else, so I don’t feel too sorry for them.

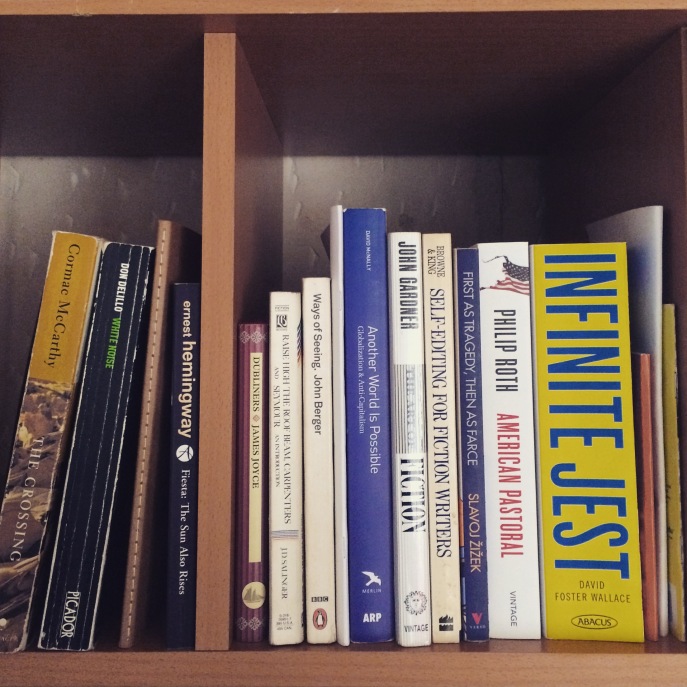

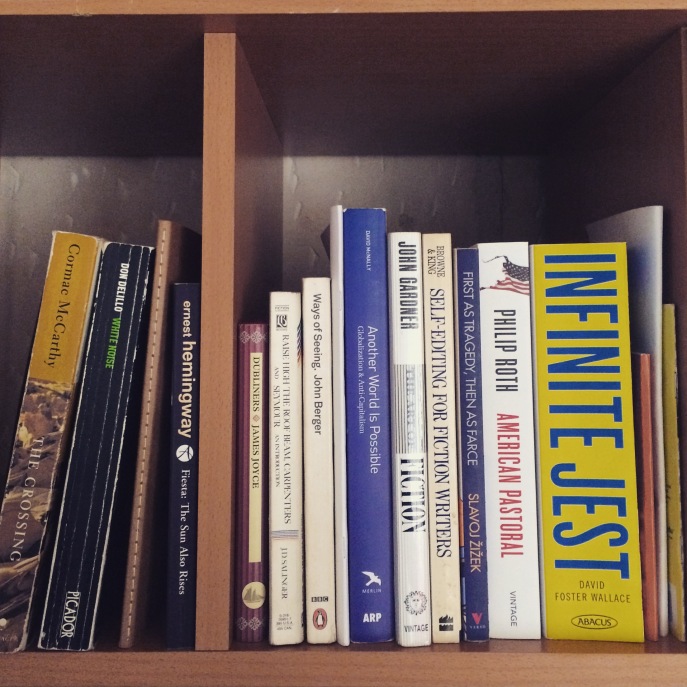

The library where I sit overlooking the river and the bridge is my library. I call it mine because it’s less than a ten minute walk from my apartment, and I kind of feel a sense of ownership for everything I can reach by foot. It’s a wonderful place to sit and read, and there are only a handful of problems with it. For one thing, it’s closed Sundays and Mondays, which forces me to haunt some other establishment where it’s customary to purchase something if you want to sit and read. The other problem is that all the books are in French. Not a big deal though–I brought a bunch of my own. One nice thing about the library is the DVD section. I can borrow two DVD’s at a time at no charge. This was especially handy during that first month when our internet was in the mail. I still borrow a film now and then because Netflix doesn’t have everything. The last complaint I have is about the people whispering. There’s a lot of whispering.

When I was in Winnipeg I bought an umbrella at Winners. It was a good umbrella and it was on sale and I read that Tours gets a lot of rain so I thought, boy, you’re really thinking ahead old man, good job. Rosie laughed that I bought an umbrella in the winter, but I told her, just wait, it’ll all make sense. It turns out that it does rain a lot here and if you have one of those tiny purse-sized umbrellas you’re okay as long as there is no wind, but when the wind picks up, look out. That’s why Rosie had to replace her tiny umbrella before we’d even been here a month. I shared my sturdy umbrella with her on the day that hers broke and I think it made sense then why I’d bought the umbrella. To be fair to Rosie, she laughed because I already had an umbrella, but that umbrella was obtrusive. I’m glad I brought this normal-sized umbrella because the streets here are narrow.

There is a young man walking through the library carrying a book bag that reads, Britney Spears Changed My Life. All I can think is, I hope that’s true.

When you get a good seat at a coffee shop you kind of want to spend the day there. There’s this place down the street from me called La Petite Atelier. I’ve been going there since the first day we arrived in Tours. In fact we went there our first evening in order to borrow their Wifi and do a money transfer. They put mint in their water. It’s a nice touch. Plus the coffee is good so I just keep going back. I suddenly wondered what the hell Atelier meant so I looked it up. It means “a workshop or studio, especially one used by an artist.” I don’t know if putting mint in the water constitutes artistry, but like I said, the coffee is pretty fucking good.

It’s hard to find spicy food here. We have a pretty good spice rack going on in our apartment, but I still haven’t found chili powder. That’s not the whole truth. I did find chilli powder, but it was way more than I was willing to pay. I think that if something is out of your price range than that thing doesn’t really exist. Like in Rome, I saw a guy driving a Ferrari, but I didn’t really see the Ferrari. All I saw was a price tag with way too big a number on it, so I had to look away and tell myself I didn’t see a Ferrari. That’s why I’m saying that I haven’t found chili powder yet.

The man with the Britney Spears bag took a book from a section called Romans de l’Imaginaire. Before I look it up I’m going to guess that that means Imaginary Romans. I looked it up. It means Fantasy Novels. I guess Romans means Novel. I was pretty close on the Imaginary bit, though.

I have an island. I’ve only been there a few times because it’s the kind of place you’d really only visit on a warm, sunny day and there hasn’t been too many of those. But I plan to go there a lot in the spring. I brought a picnic lunch there one day. Sunburned my nose, too. My lunch was a sandwich. The bread and cheese here … well, it goes without saying.

In french, umbrella is parapluie. That’s different than parasol, which is a beach umbrella. I said parasol and Rosie told me that that meant beach umbrella. Now I know the difference.

I drink a lot of wine. It’s the cheapest kind of booze you can find and it goes with almost anything. It’s a nice routine to pick up a bottle of wine and a baguette on my way home from the library. You could live off of that. I don’t live off of bread and wine, though. I eat lots of other things, too. I haven’t had tacos since December. I miss tacos.

Those are some thoughts and experiences I’ve had so far in this city. When I feel like it I may talk about our trip to Italy. I don’t know. There’s bound to be more to talk about, but it’s a little city and the pace of life is slow. We’ll see what happens.